To Give a Little Humanity

by

Justice Putnam

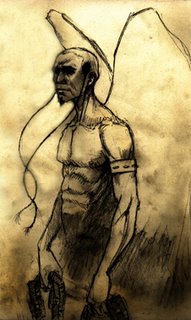

Yes, yes your Honors, I remember the boy. He was the most reticent I’d seen pass through the transfer camp. Yes, yes, quite unlike all the other children. He was most difficult. You see, we were mandated by the High Command to put these children at ease before they were transferred. So we used many means to elicit some benign emotion. To see a young one cry or to laugh meant we were successful. It would not do for them to be transferred as mere zombies. We are not cruel, nor are we uncivilized. We never tried to make those children unconscious about their lives; we wanted them to be awake and aware, as all children must be taught.

All the others had no success with him. He neither cried nor smiled; he didn’t play with the other children. He was mostly by himself but always, always, awake or asleep, he kept his right fist tight and clenched.

I was called in after a few days. The next transfer scheduled was only two days after that. I offered him candies and he refused any. Unlike any of the other children that have passed through the camp the last year. My! He was the talk of Camp!! I asked him to relax, I said that he would be taken care of and had nothing to worry about. I assured him that he would be with his parents soon; if he would just unclench his fist, we’d shake on it.

That reticent little boy ran away! No, normally, normally that would not do. Any other child would have been punished, severely. It will not do for other children to observe such a lack of authority in those circumstances. But this boy was my project and I wanted his laughs or his cries to come without force. I am after all, as I’ve stated before, neither cruel nor uncivilized.

I would sit with him and show photographs of great works of Art the High Command confiscated for protection. I read passages of literary giants from the last few books not burned. Simply being there and feeding him, so to speak, with a firm but learned affection did indeed, yes indeed, calm him.

So like a frightened puppy, that reticent little boy finally began to befriend me. He finally began to speak, to only me mind you, but his little whispers gained some trust in a very short time.

And not a minute too soon. The transfer was only minutes away.

He told me how his father was apprehended by the authorities one morning a year before. The little one cast his eyes down to the ground as he told me his story, his right fist tight and clenched. He told me of how hungry and sick his mother was; how he would scavenge for some kind of food and bring her some little thing he found.

All the while that reticent little boy told me his story, but his fist never unclenched. I could hear the fires being stoked. The drums of sarin were put in place. The children were being lined up for the transfer and I am sure the little boy had an epiphany.

Because he gazed up at me finally and held his right hand out for me to look. Some sad crumbs of an old muffin were moldy on his palm. He had been saving them for his mother, for when he would see her again. He told me she was so hungry and sick.

Then, with tears welling up in his eyes, he said he didn’t think he needed those crumbs anymore. He cried as he was transferred.

You cannot know the sense of accomplishment I had! That little boy faced his transfer with the right amount of humanity mandated by the High Command.

As I’ve said, we are neither cruel nor uncivilized.

© 2006 by Justice Putnam

and Mechanisches-Strophe Verlagswesen